I have created a project called ReadOut for 100in1Day in Canada. Begun in 2012 in Colombia, 100in1day is an act of "urban intervention" for citizens to improve their cities with simple ideas to create temporary or permanent changes to their communities. Canada's six participating cities have set June 4 as the nation's community day of action.

The urban intervention movement seems rooted in twentieth-century counterculture.In counterculture, subsections of a community build, march, and organize without the permission of official social structures, including government. 100in1Day has connections to folk carnivals and festivals, Dadaism, the American happenings and French situationists of the

1950s and 1960s, the flash mobs of the 2000s, the infiltrations of Pussy Riot, and the Occupy movements. Mimi Zeiger's The Interventionist's Toolkit catalogues 21st century urban interventionism with an emphasize on urban architecture and planning.

Dadaists

thought that art as a category should be dismantled because such

categorization gathered up the qualities of art and isolated them from other human activities, as though the values of art

had no business being integrated with human culture generally. Street

art, therefore, especially guerrilla street art such as graffitti, aims

to remedy this false categorization and return art to where it belongs: everywhere people live. This connection with street art is manifest in the

many

100in1day projects that involve visual art in some way. Murals are

popular, for example.

In the case of 100In1Day, local governments seem actively involved in promoting these interventions. Instructions for Edmonton's 100In1Day stress the need to fill out permits and follow bylaws. I suspect that municipal city planners and nonprofits are desperate to appeal to as many subcommunities as they can and therefore appreciate this self-funnelling of group energies into small-scale activities. Groups can reveal a need or a willingness to cooperate through an urban intervention, and in this display make their cause visible to others, including nonprofit and government agencies. At the same time, land developers and real estate agents, as well as other businesses, sponsor or initiate projects. As a result, some of the interest in this day has a foot in the door of private profit-making.

Perhaps 100In1Day is a cooptation of underground activism for ideological ends. My little project has people reading and waving and talking to people in their neighbourhoods. If one of the things people choose to read on their front lawns is Guy Debord's The Society of the Spectacle, so be it.

Monday, 23 May 2016

Friday, 20 May 2016

Uncheck Your Phone

|

| Tomato seeds in an egg carton |

Instead of using up those few moments of my day when I have to wait for something to happen--a file to load, a person to find his debit card in his wallet, a person to come back to the car after running out to buy some milk--I am going to do other things. Checking the phone, at least for me, sometimes takes me away not for a few seconds but for a few minutes. I can accomplish a great deal that is creative, rather than consumptive (reading ads other people have written, playing games other people have written) in those minutes.

|

| Tomato seedlings in tomato cans |

Instead of checking my phone, I have been able to do the following:

1. Make bookmarks. I started with pages torn out of a spine-cracked Jane Eyre paperback. With a few strokes of a paintbrush in a pot of Modge Podge, I can layer the paper with glue that hardens the pages so they can last for as long as those bookmarks you get at the clinic about health services.

|

| Combination of two anti-phone-checking tactics |

3. Read snippets from any book or magazine I have lying around, such Invisible Man, pictured here with a bookmark I made.

Saturday, 7 May 2016

Fiction and democracy

|

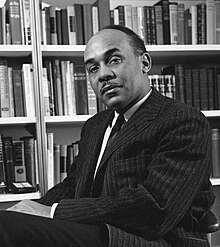

| Ralph Waldo Ellison (from Wikipedia) |

In the 1981 introduction to his 1952 novel Invisible Man, Ellison explains the genesis of his novel as a convergence of artistic ambition and "social responsibility":

"[I]t would seem that the interests of art and democracy converge, the development of conscious, articulate citizens being an established goal of this democratic society, and the creation of conscious, articulate characters being indispensable to the creation of resonant compositional centers through which an organic consistency can be achieved in the fashioning of fictional forms. By way of imposing meaning upon our disparate American experience the novelist seeks to create forms in which acts, scenes and characters speak for more than their immediate selves, and in this enterprise the very nature of language is on his side. For by a trick of fate (and our racial problems notwithstanding) the human imagination is integrative--and the same is true of the centrifugal force that inspirits the democratic process. And while fiction is but a form of symbolic action, a mere game of "as if," therein lies its true function and its potential for effecting change. For at its most serious, just as is true of politics at its best, it is a thrust toward a human ideal. And it approaches that ideal by a subtle process of negating the world of things as given in favor of a complex of man-made positives."

Ellison goes on draw an analogy from Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, in which the young white Huck goes on a river adventure on a raft with his friend and slave Jim. Their adventure constitutes a mental space "in which the actual combines with the ideal and gives us representations of a state of things in which the highly placed and the lowly, the black and the white, the northerner and the southerner, the native-born and the immigrant are combined to tell us of transcendent truths and possibilities." Fiction, then, "could be fashioned as a raft of hope, perception and entertainment that might help keep us afloat as we tried to negotiate the snags and whirlpools that mark our nation's vacillating course towards and away from the democratic ideal."

This view of creativity, then combines art, a widely recognizable avatar of creativity, with political reform. Such reform depends on the willingness to rectify dysfunction by implementing new models of governance. To create new mechanisms for governance requires, of course, creativity. Political reformers, then, as far as Ellison is concerned, could use the skills people develop in reading and writing fiction to power the "centrifugal force" that leads to a desire to modify the status quo.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)